Breaking it down

- Aws solution architect , Systems design

- September 13, 2024

- 25 min read

- Original: AWS Internal Wiki

Table of Contents

So far, our discussions have focused on critical thinking - understanding the reasons (“why”) and implications (“so what”) that help examine phenomena within a problem domain. By exploring Systems Thinking, we can understand these phenomena as interconnected components of a larger system. Defining the system’s boundaries reveals that the phenomena have upstream effects on downstream, interrelated systems, which can exhibit unexpected (“emergent”) behaviors. Effectively, the whole system is greater than the sum of its parts.

Subdomains

So, a post titled “Breaking it down” might seem a little counter-intuitive. Why are we breaking things down into smaller parts? Why not just treat the entire view as the problem domain? If these are the questions you’re thinking of, congratulations, you’re getting the hang of asking “why”. Breaking complex problems down into smaller parts makes it easier to understand how to solve the smaller more manageable parts, a principle in software engineering and systems design known as modularity. Modularity promotes: 1/ the separation of different aspects of the problem to be simplified and managed independently and 2/ the ability for each subdomain to be viewed and solved at a higher level of abstraction without getting bogged down in the details of the entire domain. When broken down from this perspective, not only can complex problems be easier to understand and manage, but we can also leverage parallelism, where different teams (or individuals) can work on different parts concurrently, enabling faster progress and reusable solutions. You have probably done this before, possibly even unconsciously.

So, let’s look at “how” to break down problems into subdomains, which comes back to having the right perspective/lens. But first, a refresher: in Systems Thinking Part 1: Interconnectivity, we talked about Pi skilling, or the importance of specialization in a primary domain with at least one secondary adjacent domain, and a high-level breadth of interrelated domains. Our focus was on the importance of having a breadth of understanding, to see the connections across domains and disciplines. In Systems Thinking Part 2: Infinity, we followed with the importance of understanding a systems boundaries and environments and the role that feedback loops have on a system from the perspective of interventions that provide the ability to adapt and evolve over time.

Having a breadth of understanding of domains and their interconnection (“integration”) along with being able to understand systems boundaries and feedback loops (“subdomains”) are the key concepts to consider when considering “how” to break down a problem. This brings us back to the importance of our knowledge domains, and just like in the infinite game, the significance of collaboration and cooperation between Subject Matter Experts who foster a shared holistic perspective.

“Because the domain experts are feeding into it, it reflects deep knowledge of the business and those abstractions are true business principles.” ― Eric Evans, Domain Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software

Within each knowledge domain are established concepts, theories, methods, techniques, terminology, and accumulated knowledge specific to that domain. Experts develop deep understanding and skills pertaining to their respective knowledge domains through education, training, and experience. This is important to remember, coupled with the understanding that we as SAs are developing software systems to solve problems that are specific to those domains.

“The heart of software is its ability to solve domain-related problems for its user.” ― Eric Evans, Domain Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software

So how do knowledge domains and business domains relate to software systems? Knowledge domains structure human knowledge, enabling specialized focus with interdisciplinary connections whereas business domains do the same for business operations or activities including the processes, entities, rules, roles, and responsibilities. Combining knowledge and business domains for system design applies the business purpose and knowledge to define subdomain boundaries. These boundaries help understand inputs, outputs, and integration within the larger system context - this is Domain-Driven Design.

Evolutionary Design

Domain Driven Design (DDD) is a software development practice that promotes an evolutionary design approach; Much like we discussed in Systems Thinking Part 2: Infinity,Thought experiment continued through the design and processes that allow the functional output the ability to consistently adapt and evolve as business requirements change.

Domain-Driven Design advocates a domain model capturing the essential business concepts, relationships, and behaviors. This model aligns the software with the real-world domain. DDD principles work well for Systems Design, where the domain model and code evolve alongside the understanding of the problem domain, including the design and configuration of services like Lambda or Containers. By breaking down the business problem into domains, we can incrementally refine and evolve each domain’s model and implementation of its solution as our understanding of the domain grows.

Separated and Bounded

It’s important to note that identifying and defining domains is not a trivial task. It requires a deep understanding of the problem domain as well as effective communication and collaboration among the stakeholders/domain specialists. This is exactly why we have built up to this discussion with understanding Critical Thinking and Systems Thinking concepts. Note that this article is not aimed at convincing you to blindly implement DDD into all your solution designs, you need to think critically to figure out where and when it is appropriate. However, any effort you invest in this process can pay off significantly in the long run.

Let’s have a look at two critical DDD concepts.

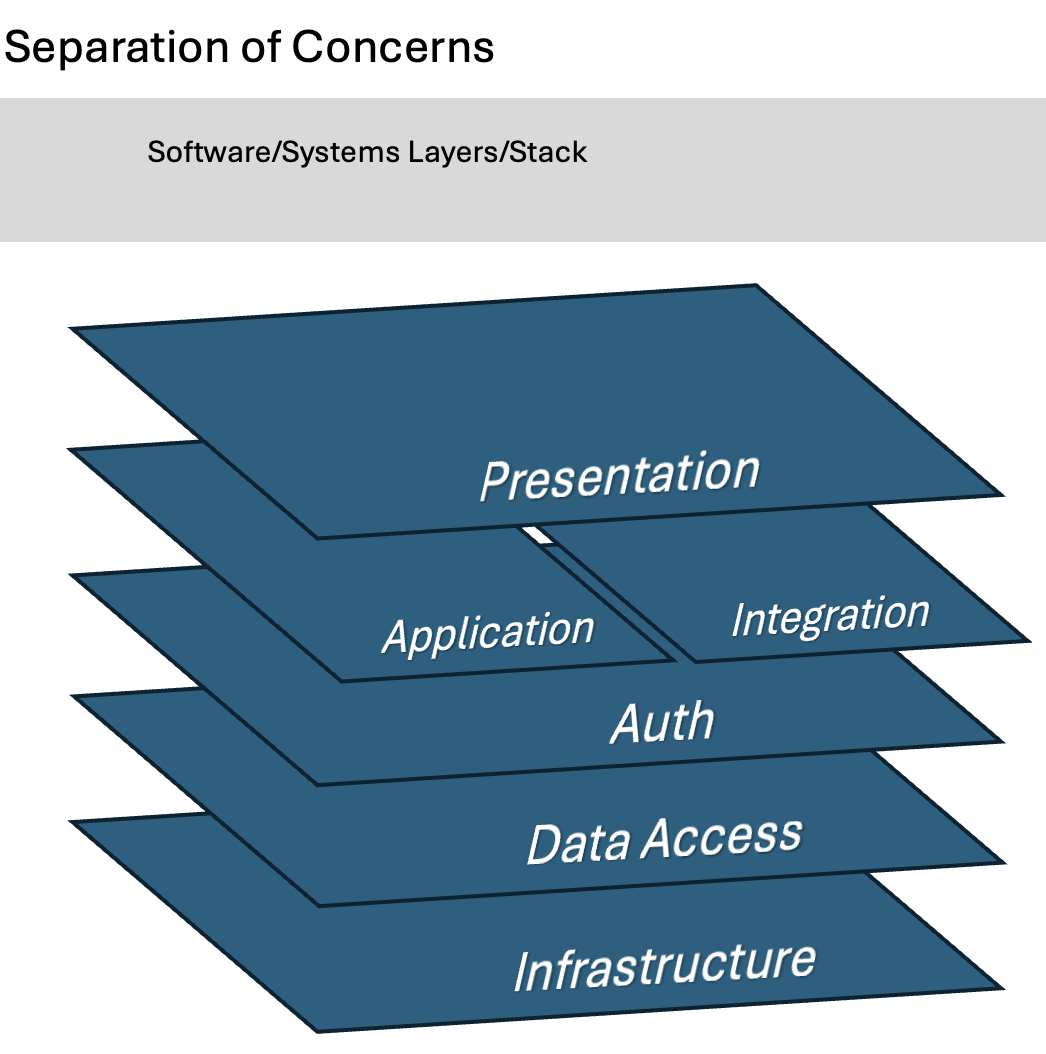

Separation of Concerns

The first concept, Separation of Concerns (SoC), is a fundamental principle in software design that promotes modular and organized system architecture. It is a design approach that emphasizes separating different aspects or ‘concerns’ of a software system into distinct modules or components, each responsible for a specific set of tasks or functionalities. The importance of SoC in systems design lies in its ability to enhance maintainability, scalability, and reusability of the system, while also promoting better code/configuration/logical organization and collaboration among developers/builders/Solution Architects.

By separating concerns into distinct modules or components, it becomes easier to understand and maintain specific parts of the system without impacting the entire solution. By separating concerns into self-contained and well-defined modules, it becomes easier to reuse these components in other parts of the system or even in different projects. Reusable components can save development time and effort, as well as promote consistency across the code-base. Here, we could discuss more than just the development of reusable solutions (Design Wins); we could also talk about libraries, packages, or constructs (AWS CDK constructs) that are at the heart of platform design and development.

SoC helps us in organizing the logical structure of our solutions. Making it easier to navigate and understand the system’s architecture. This is particularly beneficial for large and complex systems, where having a clear separation of concerns can significantly improve maintainability.

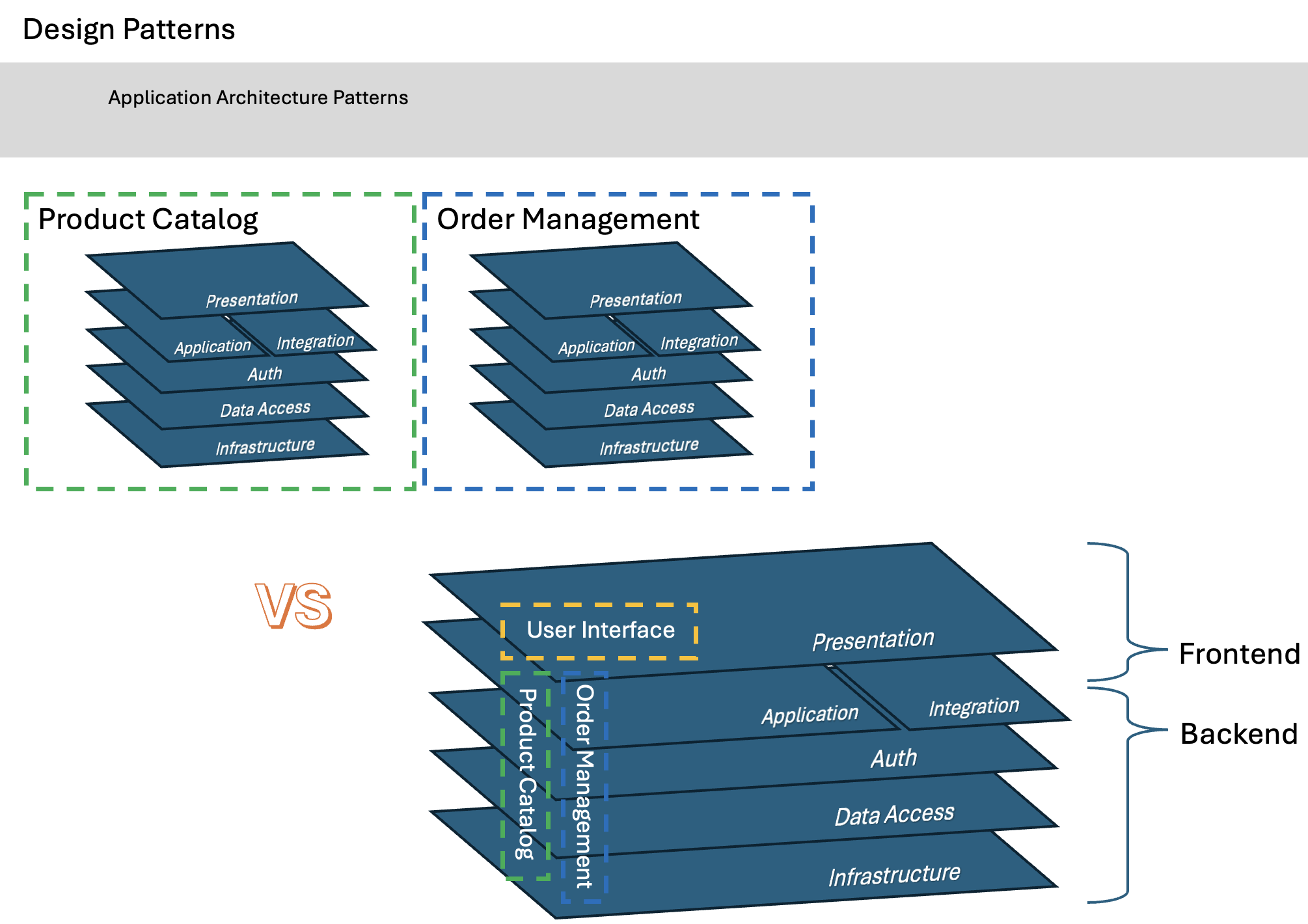

As an example, consider we are developing a web-based e-commerce application to sell books online. This e-commerce application needs to allow users to browse the books, add books to a shopping cart, and complete the checkout process. In a solution like this, the SoC is traditionally separated into different layers (commonly known as a “Stack”); The Presentation Layer (User Interface) is responsible for handling user interactions and rendering the visual elements of the application. The Application Layer (Business Logic) handles the core business logic and rules of the application. The Data Access Layer is responsible for interacting with the underlying data storage system (e.g., databases, file systems, caches). The Authentication and Authorization Layer Handles user authentication (e.g., login, registration) and authorization (determining access permissions). The Integration Layer facilitates communication and data exchange with other subsystems, external systems and/or third-party services. The Infrastructure Layer provides common services and utilities required by the application, such as logging, caching, messaging, configuration management, and compute for virtualization or cluster management for containers.

By separating these concerns into distinct layers or components, the application becomes more modular, maintainable, and extensible. Each layer or component can be developed, tested, and deployed independently, making it easier to manage complexity, isolate changes, and facilitate collaboration. For example, if the application needs to integrate with a new payment gateway, the changes will primarily affect the Integration Layer, leaving the other layers relatively untouched. Similarly, if the business rules for order processing change, the modifications would be confined to the Application Layer, without impacting the Presentation Layer or Data Access Layer.

However, it is important to understand the balance between over-separation and under-separation of concerns. Over-separation can lead to an overly complex and fragmented system, while under-separation can result in tightly coupled components and reduced maintainability. Proper application of design principles and patterns, such as the Single Responsibility Principle, Dependency Inversion Principle, Open-Closed Principle, and Separation of Concerns itself, can help achieve the right balance and maximize the benefits of this approach. (use your critical thinking here: Learn and develop an understanding of the SOLID Principles, understand how SOLID can be applied beyond coding, and into Systems Design)

When considering complex problems and breaking them down into smaller more manageable domains, SoC facilitates better collaboration between technology domains by allowing them to work as different modules or concerns concurrently without causing conflicts or duplicating efforts. However, the breakdown of technology domains for separation of concerns does not help to facilitate the business domain or subdomains for the business problem we are attempting to solve.

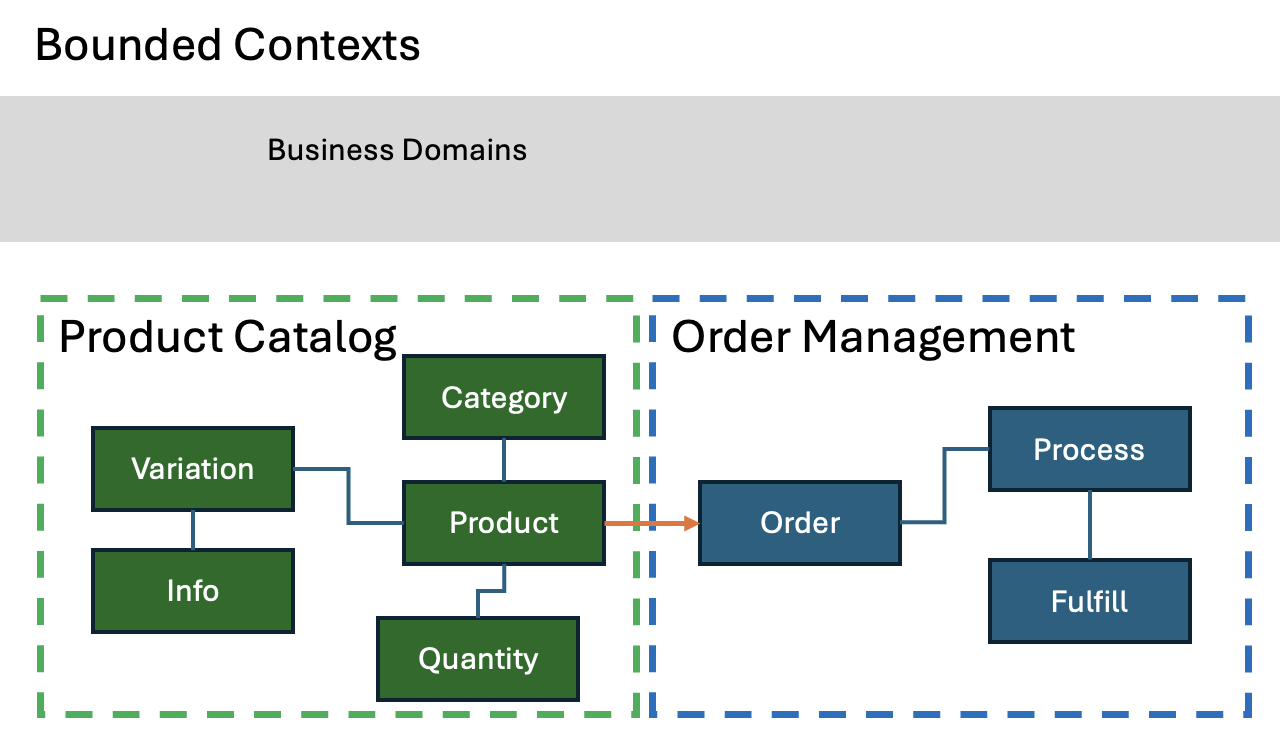

Bounded Contexts

This brings us to the second concept, and back to the lessons we learned in the discussion of Systems Thinking, specifically understanding where and how we define our boundaries. In DDD, these subdomain boundaries are called Bounded Contexts They provide a way to define the separation of concerns for the different parts of our system from the business domain context. Each Bounded Context represents a specific area of the domain (or business), with its own language, models, and rules.

As an example, in our e-commerce platform the business domains would be divided into how separate parts of the business are managed and interact. Such as the Product Catalog: the context that manages the product information, the variations, the categories and tags and even the total inventory quantity. This is different to the Order Management: the context that manages the creation, tracking and fulfillment of orders. Just like the physical business, the product inventory and order management are all managed by different teams, so they should be separated into distinct bounded contexts.

However, we still need to view the Bounded Contexts through the Systems Thinking lens and recognize they do not exist in isolation; they exist in the larger context of the environment (or larger system) and interact with other bounded contexts within the system. We therefore need to define the relationships and communication patterns between different Bounded Contexts, this is known as Context Mapping. This helps in managing the dependencies and interactions between contexts, promoting better system integration and maintainability. And defines how they are implemented through well-defined interfaces or integration mechanisms, such as messaging, APIs, or event-driven architectures, to maintain the separation of concerns and prevent coupling between contexts.

Design by Pattern

Patterns are not a new concept. In fact, an architect (of buildings), Christopher Alexander, is widely regarded as the father of the pattern movement. One of the more famous patterns is about how to construct a room (hint: humans like a room with windows on at least 2 walls!) But enough about that kind of architecture, let’s get back to our domains.

So, once you have identified the Bounded Contexts, it is essential to map the relationships between them. This includes defining how contexts communicate with each other, whether through shared models, anti-corruption layers, or other integration mechanisms. Managing these interdependencies while maintaining separation of concerns can become complex, especially in large, distributed systems. Speaking of complexity, you need to know about Conway’s Law.

Application architecture patterns (Design patterns) play a crucial role in mitigating the challenges posed by Conway’s Law, Bounded Contexts, and Separation of Concerns by employing well-designed, tested, and applied patterns. We will probably end up having a deeper discussion in a future article, but it’s always fun to do a teaser!

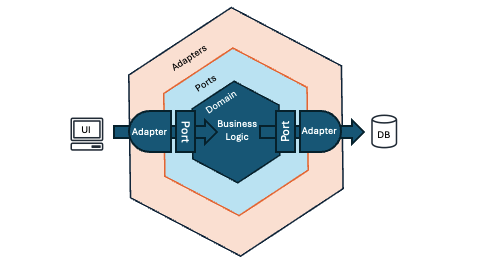

Application architecture patterns provide guidelines and structures for software components and manage their interactions. For instance, patterns like Hexagonal Architecture (Ports and Adapters) or Onion Architecture promote the separation of concerns by isolating the core business logic from external dependencies (such as user interfaces, databases, or third-party services). These patterns enable teams to work on different aspects of the system independently while adhering to well-defined interfaces and communication protocols.

Application architecture patterns often incorporate the principles we discussed earlier, like the Dependency Inversion and the Open-Closed Principles, which further reinforce the separation of concerns and promote loose coupling between components. By adhering to these principles, we can evolve and modify individual components or bounded contexts without introducing unintended ripple effects throughout the entire system.

As an example, when Separation of Concerns and Bounded Contexts are applied together, they often lead to the following common application architecture patterns:

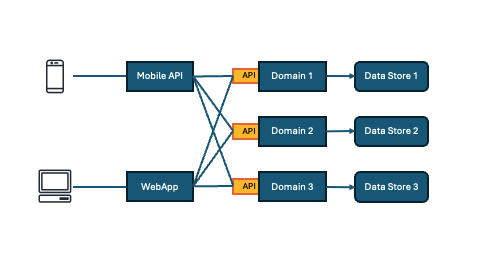

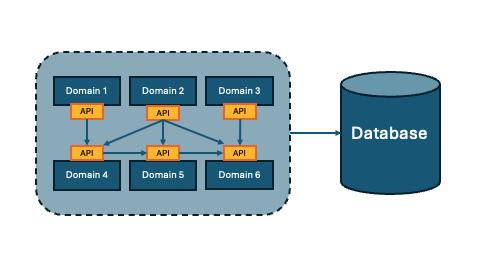

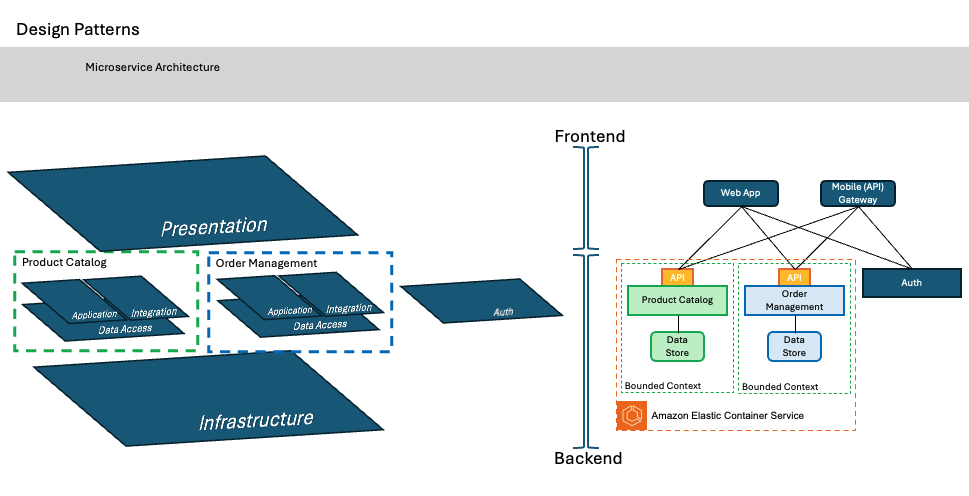

| Microservices Architecture: The application is decomposed into small, autonomous services organized around Bounded Contexts. Each microservice encapsulates a specific business capability or domain and adheres to the principle of Separation of Concerns. This architecture pattern enables independent development, deployment, and scaling of individual services, promoting agility, resilience, and scalability. |

| Modular Monolith: The application is structured as a single deployable unit, but its internal components are organized into modules or layers based on Bounded Contexts and Separation of Concerns. Each module or layer encapsulates a specific domain or subdomain, promoting code organization, maintainability, and potential for future decomposition into microservices. |

| Hexagonal Architecture: Also known as Ports and Adapters, is an architectural pattern that promotes the Separation of Concerns between the application’s core domain logic and the external dependencies (e.g., user interfaces, databases, external services). Bounded Contexts are used to define the core domain logic, while the external dependencies are isolated into separate components (adapters) that communicate with the core through well-defined interfaces (ports). |

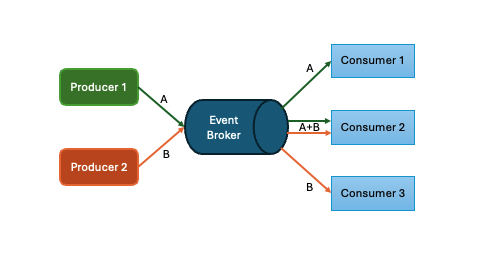

| Event-Driven Architecture: The application is decomposed into distinct components or services that communicate through events or messages. Bounded Contexts are used to define the boundaries and responsibilities of these components, while Separation of Concerns ensures that each component focuses on a specific concern or responsibility related to handling events or producing events. |

These application architecture patterns provide guidance on how to enable better modularization, maintainability, scalability, and adaptability of complex systems. They promote loose coupling between components, facilitate independent evolution of different parts of the system, and align the architecture with the underlying business domains or subdomains. But it is still up to us to understand which patterns to apply and what the Bounded Contexts and Separation of Concerns translate to within the chosen pattern.

As an example, we have already looked at how we would break our e-commence platform into business domains according to how parts of the business are managed, dividing into components such as Product Catalog and Order Management. We could design the technical solution according to any of the above patterns. However, knowing that this solution will have thousands of distinct users, which will require the ability to scale independent components of the system in isolation from other components, to support different users at different stages of their purchasing journey. The Microservice architecture pattern seems the obvious fit for what we need to achieve. The Microservice pattern promotes better scalability and flexibility by breaking down the application into smaller, independently deployable services, allowing different components of the application to scale independently based on demand. As well as better isolation and fault tolerance, as failures in one service do not necessarily impact other services. Let’s assume we will build this using ECS.

With our Bounded Contexts already defined focusing on specific components of the users’ book purchasing journey. How do we apply Separation of Concerns to our solution? Let’s consider our isolated services (bounded contexts) in the context of the layers within Separation of Concern. Firstly, we know each service manages a specific domain, so the Application Layer specific to each domain is separated into the bounds of each service. Next, in a microservice architecture, each service typically has its own database or data store. Therefore, we know the Data Access Layer will be managed within the bounds of each service. By extension, if other services within the microservice architecture require the data of another service, than they must request that data without directly accessing the first service’s data store. We can therefore extrapolate that the Integration Layer will be managed by each service through defined interfaces, such as APIs. And we know we are building the services into containers using ECS, so our Infrastructure Layer layer is defined as a cross-cutting concern outside of but supporting the isolated services.

Finally, the microservice pattern commonly separates the Presentation Layer into different components based on device type, such as web or mobile. This separation allows for better organization, scalability, and flexibility in delivering the user interface (UI) and user experience (UX) tailored to specific devices and platforms. The presentation layer ‘apps’ are responsible for rendering the UI and consist of presentation and integration logic only, to communicate with the backend microservices through APIs where all the business logic is handled. The separation of logic from the Presentation layer and the backend also means that the UI can remain stateless, providing additional fault tolerance from issues within the UI. This separation also promotes reusability and scalability, as the same backend microservices can be consumed by multiple presentation layers, serving different device types with a consistent set of data and functionality.

Fun question for you: if you were to set a discount on a product, where would you do it? and why?

Conclusion

Breaking down complex problems into manageable domains is crucial for effective systems design. As SAs, we need to be able to look at macro and micro views of systems. Concepts like Separation of Concerns and Bounded Contexts that originate from Domain-Driven Design provide a powerful toolkit to break down business problems into technical domains while preserving system integrity.

However, applying these concepts requires deep domain expertise and architectural pattern knowledge. Ultimately, breaking down problems is about leveraging modularity, abstraction, and domain-focused design to create manageable, adaptable solutions. By embracing a mindset of continuous learning, collaboration, and iterative refinement, we can navigate the complexities of modern software systems and deliver solutions that truly address the needs of the business and its customers.

Resources

- Domain-Driven Design - Eric Evans

- Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture - Martin Fowler

- Application Architecture blog - Martin Fowler

- Implementing Domain-Driven Design - Vaughn Vernon

- SOLID Principles in Object Oriented Design - Stephen Watts

- Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software - Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, John Vlissides

- Gang of Four (GoF) Design Patterns - Further examples of ‘Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software’