Systems: Definitions and Observations

- Systems design

- August 16, 2024

- 40 min read

Table of Contents

What is a System?

This post is intended as an introduction to provide a basic understanding of systems. It does not attempt to cover all the foundations of systems theory in computer science. If you are well versed in systems theory then you can skip this and post and go to Systems Thinking. For everyone else, to understand what ‘systems thinking’ is and what it hopes to achieve, we must first understand what a system is.

The oxford dictionary defines a system as:

noun

a set of things working together as parts of a mechanism or an interconnecting network; a complex whole.

“the state railway system”

a set of principles or procedures according to which something is done; an organized scheme or method.

“the public school system”

These two definitions provide two very different perspectives on systems, the first of physical “’things’” or elements that interconnect to make up something greater than its parts, and the second a set of rules and procedures that govern a practice. Each of these perspectives alone can be considered a type of system, but equally both perspectives together form a more comprehensive description of a system.

In computer science, systems theory defines a system as having causal boundaries, being influenced by its context, defined by its structure, function and role, and expressed through its relationships with other systems.

A system is a group of interconnected or interrelated elements (causal boundaries) governed by a set of rules (context and role) that guide how each element acts and interacts (function and role) as a unified whole (structure).

Characteristics of a System

Purpose

A system exists for a specific reason or purpose. The remaining characteristics of the system work together toward achieving the overall objective or function of the system.

When designing a system, the purpose is identified early as a guide to the fundamental reason for the systems existence and how the system needs to be constructed. The internal elements and processes of the system are designed specifically to fulfill the defined purpose.

The purpose of the system also provides a benchmark for evaluation. A system can be evaluated through performance metrics against how well the system fulfills its purpose. Having a benchmark for evaluation is specifically important as systems evolve. While the high-level purpose of a system usually remains stable, the specifics of objectives of the system may evolve over time as external conditions and requirements change.

This leads to the context of the system. A systems purpose depends on the larger context and environment in which it operates. The same system may serve different purposes in different contexts.

Boundaries

To understand where and how a system operates in the larger context and environment we must define the systems Boundaries. This means choosing which elements are inside the system and which are outside. The elements outside the systems boundaries, are therefore considered the external environment.

The elements inside the boundaries are the components of the system that together work to achieve the objective or purpose. The boundary therefore establishes the systems identity and distinguishes it from its environment.

The boundaries of a system can be both physical, like the walls of a room, or conceptual, like the edges of a team, and closed/rigid, where the system does not interact with its environment, or open/porous, where the system interacts with its environment across the boundaries.

The evolution of a system can be influenced by its boundaries, as equally the boundaries can influence the evolution of the system, as boundaries are not always fixed. They can expand, contract or change over time as components within the system or the external environment changes.

Elements/Components

The inside of a systems boundaries is comprised of multiple elements or components that connect and work together as a whole. The components are the building blocks that make up the entire system which can be can be physical, like engines in a car, or intangible like processes, data, or software.

Components of a system do not exist in isolation, they are interconnected through defined relationships or interfaces that allows them to work together and are often interdependent requiring inputs or outputs of other components of the system.

Components are often organised into hierarchies of components and sub-components as well as importance. Where top-level components are made of smaller sub-components, and some components may be more critical to the overall functioning of the system than other components. Critical or essential components are often called the Core components and are higher in the hierarchy of importance than non-critical components.

Each component within the system serves a specialised function. The system depends on each component to carry out its designed function which may depend on interaction with other components, while its function remains self-contained.

As functional components become more complex within the context of the larger system, they are often separated into modules classified as subsystems that define the purpose and boundary of the subsystem. Adopting a modular architecture allows subsystems to be separated and interchanged and/or reused or recombined in different systems. This facilitates efficiency and managing complexity within the system.

Inputs and Outputs

Much like the components of a system are connected and require inputs and produce outputs which may in turn feed as inputs into other components, so two a key attribute of a system is the definition of its Inputs and Outputs. In the context of a system, the Inputs and Outputs are the things that cross in and out of the system boundary.

Inputs provide some form of information, energy or material that enters the system from outside its boundaries. Inputs are consumed or transformed by the system to keep it functioning.

Outputs are the results, outcome or product that the system delivers back to its external environment. Outputs exit the system across its boundary.

The types of input/output depend on the nature of the specific system and its environment, and depending on its nature a system can have multiple differing inputs and outputs. A manufacturing system will have physical inputs such as multiple different raw materials, and outputs according to the product being developed, while an information system will have data inputs and outputs.

Inputs initiate and provide the fuel for the system’s internal processes to operate. The system’s internal process utilizes the inputs to create the outputs based on the systems purpose and functions. The outputs depend on the inputs and the outputs may provide feedback to help regulate further inputs. This feedback loop helps systems to self-regulate.

Regulation

Systems require some method of regulation or control to maintain stable operations in the face of external disturbances. Keeping the system on track despite changes in the environment is known as homeostasis.

Having defined a systems purpose and therefore a benchmark for evaluation, defining controls for the regulation of the systems health starts with the feedback loops that provide data on the outputs and current state of the system. This allows detection of deviations from desired operating parameters.

When deviations are detected, control mechanisms trigger compensating actions that adjust processes or inputs to bring the system back to the goal state. Allowing the system to adapt its processes over time in response to environmental changes and evolving requirements.

Regulation requires oversight and control at multiple levels, from basic negative feedback loops to higher authorities managing subsystems. The ability to self-regulate is an emergent property of complex systems, arising from many regulatory interactions between components.

Important

The regulation of a system often involves tradeoffs between stability, responsiveness, efficiency, and fragility. Tighter control risks being too rigid. Looser control risks instability.

Failures in regulation can propagate through a system since components depend on proper regulation. This can lead to unpredictable, unstable behavior.

Emergence

Systems exhibit emergence, referring to the appearance of novel properties or behaviors that arise due to the interactions between the systems components and which cannot be deduced from the properties of the individual components themselves.

Emergence represents one of the most fascinating aspects of complex systems, producing something more complex than what the individual parts can generate independently. Meaning the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

A key aspect of defining emergent behaviors is that they cannot be understood or predicted by breaking down the system and analyzing its components in isolation. There is no central control directing the emergent behavior. It arises naturally from distributed local interactions under a given set of conditions.

Emergent properties are often surprising compared to the individual components. They represent fundamentally new characteristics of the system that often allow the systems to adapt to achieve goals in changing environments without explicit commands.

System Archetypes

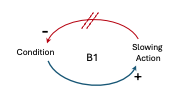

Balancing Process with Delay

| The “Balancing Process with Delay” archetype describes a delay between the occurrence of an event and the corresponding corrective action. This delay can be due to various factors, or the inherent nature of the balancing process itself. Corrective action is taken to counter a gap between the desired and actual state, but the corrective action takes time to have an effect, leading to potential overshooting or oscillations before reaching equilibrium. Example: Consider a system that consists of multiple instances of a container app (or micro-service) running on different servers, and a load balancer that distributes incoming requests among these instances. The load balancer aims to distribute the load evenly across all instances to ensure optimal performance and resource utilization. Under normal operating conditions, the load is evenly distributed across all instances. However, in the case of surging traffic, some instances become overloaded while others remain underutilized. The load balancer monitors the load on each instance and detects this imbalance. However, due to the inherent delay in collecting and processing monitoring data, there is a delay before the load balancer can react to the imbalance. During this delay, the overloaded instances may become overwhelmed, leading to increased response times, request timeouts, or even failures. Conversely, the underutilized instances remain idle, wasting valuable resources. After the delay, the load balancer adjusts its load balancing strategy to redistribute the incoming requests more evenly across all instances. This could involve techniques like weighted round-robin, least connections, or even dynamic instance provisioning (elastic scaling: scaling out or scaling in instances based on demand). As the load balancers corrective actions take effect, the overloaded instances gradually become less saturated, and the underutilized instances start receiving more requests. Over time, the system reaches a new balanced state, with the load evenly distributed across all instances. In this example, due to the initial delay in detecting and responding to the imbalance, the system experienced a period of degraded performance and potential failures before the corrective actions could take effect. This illustrates the Balancing Process with Delay archetype, where there is a delay between the detection of an imbalance and the system’s ability to take corrective action to rebalance the load. This delay can have negative consequences, such as decreased performance or failures, until the system reaches a new balanced state. |

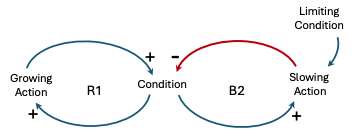

Limits to Growth

| The “Limits to Growth” archetype describes a situation where a reinforcing process eventually encounters a limiting condition or constraint, leading to a shift in the system’s behavior. Continuous growth or expansion encounters constraints or limits, leading to a potential decline or collapse. The growth phase is caused by a reinforcing feedback process (or by several reinforcing feedback processes). The slowing arises due to a balancing process brought into play as a “limit” is approached. The limit can be a resource constraint, or an external or internal response to growth. The accelerating collapse (when it occurs) arises from the reinforcing process operating in reverse, to generate more and more contraction. Example: Imagine a distributed system that initially consists of a few core services, such as an authentication service, a data storage service, and a few business logic services. As the system gains popularity and more users join, the demand for new features and functionalities increases. To meet these demands, new services are introduced, and existing services are updated or extended. Initially, the system may work efficiently, with services communicating smoothly and processing data quickly. However, as the number of services and their interdependencies increase, the complexity of the system grows exponentially. This complexity can lead to various challenges, such as:

In this scenario, the “Limits to Growth” archetype manifests as the system reaches a point where further growth and scaling become increasingly difficult due to the compounding effects of complexity, resource constraints, and operational challenges. The system may experience performance degradation, increased latency, and even outages if the growth is not managed effectively. |

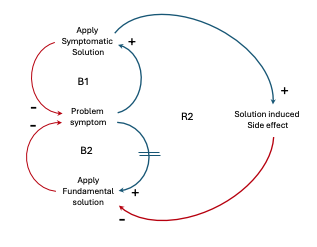

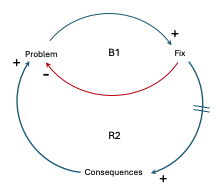

Shifting the Burden

| The “Shifting the Burden” archetype is a common pattern observed in complex systems where a quick-fix solution is implemented to address a problem, but this solution ends up becoming a dependency, masking the underlying issue and potentially making the system more vulnerable in the long run. Example: A system containing multiple micro-services handles various functionalities. One of the services, the “Order Processing Service,” is experiencing performance issues due to a high volume of requests. Initially, the team decides to implement a caching mechanism as a temporary solution to reduce the load on the service. While the caching solution helps alleviate the performance problems in the short term, it also introduces new complexities and dependencies. The system now relies heavily on the caching mechanism, which becomes a critical component. If the caching mechanism fails or becomes inconsistent, it can lead to data inconsistencies and potential issues in the overall system. The underlying root cause of the performance issue, such as inefficient database queries, sub-optimal coding practices, or architectural limitations, remains unaddressed. The team becomes complacent with the caching solution and neglects to investigate and address the fundamental problem. Over time, the caching mechanism becomes deeply ingrained in the system, making it increasingly difficult to remove or replace without causing significant disruptions. The system’s complexity grows, and the team finds itself in a situation where they are constantly maintaining and fine-tuning the caching solution, diverting resources away from addressing the root cause of the performance problem. To break free from the Shifting the Burden archetype in this scenario, the team would need to take a step back and critically analyze the root cause of the performance issue. They might need to refactor the code, optimize database queries, or even rethink the overall architecture of the Order Processing Service. By addressing the underlying problem, the team can potentially eliminate the need for the caching solution or at least reduce its criticality, making the system more resilient and easier to maintain in the long run. The Shifting the Burden archetype serves as a reminder that while quick-fix solutions can provide temporary relief, they should not become a long-term dependency. It’s essential to address the root causes of problems to build robust and sustainable systems. |

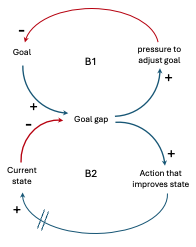

Eroding Goals

| The “Eroding Goals” archetype can manifest when the overall goals or objectives of the system gradually become compromised or diluted due to various factors over time. This can lead to a misalignment between the intended purpose of the system and the actual functionality or behavior it exhibits. Example: a company develops a distributed e-commerce platform built on a service-oriented architecture. The initial goal was to create a highly scalable, reliable, and efficient system that provides seamless shopping experiences for customers and streamlines order fulfillment processes for merchants. At the outset, the system was designed with a clear separation of concerns, modular services, and well-defined interfaces. However, over time, as new features were added, deadlines were tightened, and development teams changed, certain compromises were made to meet short-term objectives. Initially, some services were coupled tightly to expedite development, and cross-cutting concerns like logging and error handling were not consistently implemented across all services. These small deviations from the initial design principles gradually accumulated, leading to an erosion of the system’s goals. As a result, the system became increasingly complex, with services that were difficult to maintain and scale independently. Performance issues arose due to inefficient data access patterns and excessive network communication between services. The reliability of the system suffered from inconsistent error handling and lack of proper monitoring and failure recovery mechanisms. While the e-commerce platform still functioned and met some of the original goals, the overall quality, maintainability, and scalability of the system eroded over time, deviating from the intended design and objectives. This erosion made it increasingly challenging to introduce new features, address performance bottlenecks, and adapt to changing business requirements. In this example, the Eroding Goals archetype manifested due to a combination of factors, such as pressure to meet short-term deadlines, lack of adherence to design principles, and insufficient governance over the system’s evolution. The initial goals of scalability, reliability, and efficiency were gradually compromised, leading to a system that fell short of its intended purpose and became increasingly difficult to manage and evolve. |

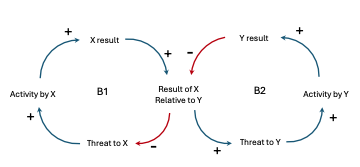

Escalation

| The “Escalation” archetype is a pattern that helps manage exception situations or failures. It defines a strategy for handling failures or issues that cannot be resolved at a lower level of the system by escalating them to higher levels or different components for resolution. When uncontrolled the Escalation archetype can be a vicious cycle where a solution leads to unintended consequences, prompting another solution that worsens the original problem. Example: Our e-commerce system is composed of several services, including an Order Service, Payment Service, and Inventory Service. The Order Service is responsible for handling customer orders, interacting with the Payment Service for processing payments, and communicating with the Inventory Service to check and update stock levels. In this scenario, the Escalation archetype could be implemented as follows:

By implementing the Escalation archetype, a distributed system can handle failures and exception situations in a structured and scalable manner. Each level of escalation can apply appropriate strategies and leverage specialized components or services to resolve the issue effectively. It’s important to note that the specific implementation details and escalation levels will depend on the requirements, complexity, and design of the system. |

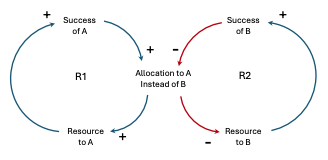

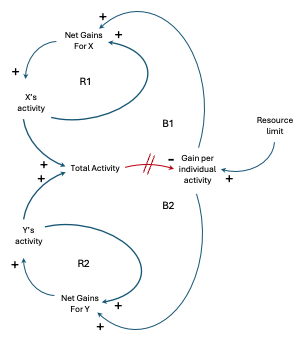

Success to the Successful

| The “Success to the Successful” archetype, also known as the “Matthew Effect,” describes a phenomenon where resources and opportunities tend to accumulate for those who are already successful, while those who are less successful often struggle to gain traction. Two activities compete for limited resources. The more successful one becomes, the more resources one gains, thereby starving the other. Example: A distributed system consisting has multiple micro-services, each responsible for handling a specific set of tasks. One of these micro-services, “Service A,” is particularly well-designed and efficient, providing fast and reliable responses to client requests. As Service A gains a reputation for its performance, more and more clients start using it, leading to an increase in the number of requests it receives. This increased load prompts the system administrators to allocate more resources (CPU, memory, network bandwidth, etc), allowing it to handle the growing demand effectively. On the other hand, another micro-service, “Service B,” may not be as efficient or well-designed as Service A. It has longer response times and occasional failures, leading to a poorer reputation among clients. As a result, fewer clients utilize Service B, and it receives fewer requests. Due to the lower demand for Service B, the system administrators do not prioritize allocating additional resources to it, as they perceive it as less critical compared to the highly utilized Service A. This lack of resource allocation can further exacerbate Service B’s performance issues, making it even less attractive to potential clients, creating a self-reinforcing cycle. In this scenario, Service A’s initial success attracts more resources and opportunities, allowing it to improve further and become even more successful. Conversely, Service B’s relative underperformance leads to fewer opportunities for improvement, making it harder for it to catch up with the more successful Service A. The “Success to the Successful” archetype can create imbalances and inequalities within a system, where some services thrive while others struggle to gain traction. To mitigate this effect, system architects and administrators may need to actively monitor and allocate resources to ensure fair distribution and prevent a concentration of resources on a few highly successful services at the expense of others. |

Tragedy of the Commons

| The “Tragedy of the Commons” archetype can manifest itself when multiple services or components share and overuse a common resource, leading to its depletion or degradation. Actors use a commonly available but limited resource solely on the basis of individual need. At first they are reward for using it; eventually, they get diminishing returns, which causes them to intensify their efforts. Eventually, the resource is either significantly depleted, eroded, or entirely used up. Example: Consider a shared database cluster. Multiple services within the system rely on this database cluster for storing and retrieving data. Each service is designed and developed independently, with the assumption that the database cluster has ample resources to handle their requests. When the system is lightly loaded, all services perform well, and the database cluster can handle the requests efficiently. However, as the system scales and more services are added or existing services experience increased load, the shared database cluster becomes a bottleneck. Each service, focused on optimizing its own performance, starts to make more frequent and resource-intensive queries or transactions on the database cluster. This behavior can lead to the following consequences:

In this scenario, the Tragedy of the Commons occurs because each service acts in its own self-interest, consuming shared database resources without considering the impact on the overall system. As a result, the shared resource (the database cluster) becomes depleted or degraded, negatively impacting all services that rely on it. To mitigate this issue, various strategies can be employed, such as:

By proactively managing and governing the shared resources in a service-oriented distributed system, the Tragedy of the Commons can be mitigated, ensuring the system’s overall health and performance. |

Fixes that Fail

| The “Fixes that Fail” archetype describes the situation where a quick-fix solution to a problem creates unintended consequences or new problems that ultimately worsen the original issue. Example: A service responsible for processing customer orders in an e-commerce application, over time, as the number of users and orders increases, starts to experience performance degradation, leading to slow response times and potential customer dissatisfaction. To address this issue, the team decides to scale out the order processing service by deploying additional instances of the service across multiple nodes or servers. The assumption is that distributing the load across multiple instances will alleviate the performance bottleneck. However, in a distributed system, there might be underlying architectural or design issues that are not adequately addressed by simply scaling out a service. Such as:

In such scenarios, the “fix” of scaling out the order processing service could fail to address the underlying performance issues or even introduce new problems, such as increased complexity, data consistency challenges, or resource contention. The team might end up with a more distributed system that still suffers from performance degradation, leading to further frustration and wasted efforts. The “Fixes that Fail” archetype highlights the importance of thoroughly understanding the root causes of performance issues in distributed systems and considering the broader architectural implications before implementing “quick fixes” like scaling out individual services. |

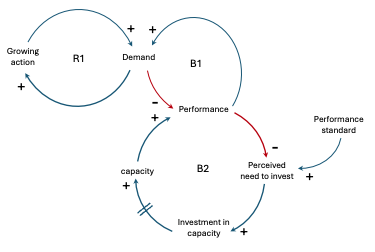

Growth and Underinvestment

| The “Growth and Underinvestment” archetype describes a situation where growth leads to a shortage of capacity, which then inhibits further growth due to underinvestment in capacity expansion, creating a vicious cycle. Example: Our system contains various micro-services, such as an authentication service, an order management service, and a payment service. The system is designed to handle a certain level of traffic and workload. As business grows, the demand for the system’s services increases. To meet this growing demand, the company scales out the micro-services by adding more instances or nodes to handle the increased traffic. However, as the system continues to grow, the underlying infrastructure, such as databases, message queues, and other supporting services, may not be adequately scaled or invested in to accommodate the increased load. This can lead to performance bottlenecks, latency issues, and potential system failures. For example, the database hosting the order management service may become overwhelmed due to the increased number of order requests, resulting in slow response times or even outages. Similarly, the message queue responsible for handling the communication between the payment service and other services may become a bottleneck, leading to delayed or lost messages. In this scenario, the Growth and Underinvestment archetype manifests as the focus primarily on scaling out the micro-services themselves without adequately investing in the supporting infrastructure and services. While the system initially grows to meet the increasing demand, the lack of investment in the underlying infrastructure eventually leads to performance degradation, stability issues, and potential system failures. To address this archetype, proactively monitor and invest in the supporting infrastructure and services as the system grows. This may involve scaling out databases, upgrading message queues, optimizing network configurations, or even refactoring parts of the system to better handle the increased load. Failing to address the Growth and Underinvestment archetype can ultimately lead to system instability, customer dissatisfaction, and potential business losses. |