Systems Thinking Part 1: Interconnectivity

- Aws solution architect , Systems design

- August 16, 2024

- 20 min read

- Original: AWS Internal Wiki

Table of Contents

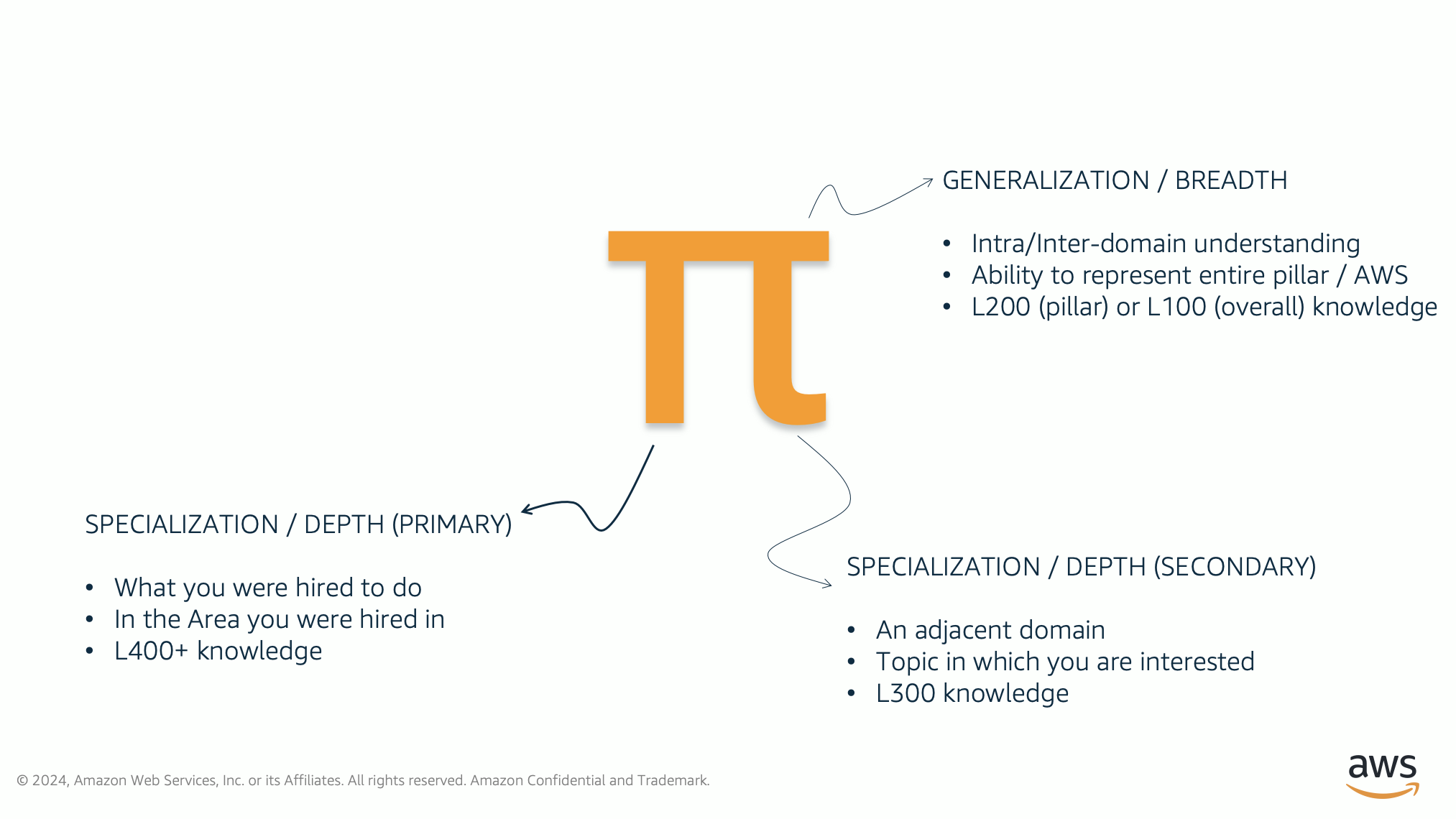

Breadth and Depth

In the two preceding articles in this series, you may have recognized a trend on digging deeper to get to the “depth” of Solution Architecture. We started with a high level understanding of what makes a great SA by applying critical thinking skills, then dug deeper into how to get an understanding of the rationale (“why”) and implications (“so what”) behind the situational context, problem statement, potential solutions, personal focus, goals, and consequences of any actions.

Digging into the “depth” of a subject allows us to attain proficiency in that specific area or subject matter so that we can tackle complex problems. But here’s the rub: just having depth is not enough. It is important to have a balance between the depth of a subject and the breadth of its wider context. You may be a Specialist SA thinking “this doesn’t apply to me, having a breadth is for generalist SAs, specialists are all about our depth of domain”. If that’s what you think, you are only half right! Yes, specializing is about understanding a domain deeper than (most of) our generalist counterparts. But while depth allows us to delve into specific areas and develop specialized expertise, having a breadth of knowledge allows us to see connections across different domains and disciplines. It promotes interdisciplinary thinking, creativity, and the ability to approach problems from multiple perspectives.

A Specialist SA focuses different levels of time and effort depending on the domains: 1/ often focusing the most into a primary domain (L400+), 2/ applying a slightly lesser effort on a secondary or adjacent domain (L300), and 3/ having a high-level understanding across many related domains (L100). This is known as Pi skilling.

A generalist SA however, spreads their effort, learning and practice more evenly across a breadth of domains where they generally focus to a moderate depth across domains (L200 to L300), deeper than the breadth of a Specialist SA, but generally not to the same depth of a Specialist SAs primary domain (L400). Fascinatingly, with time and experience, generalist SAs will often become Pi skilled.

The importance here is on the breadth of knowledge as this prevents ’narrow specialization’ and with the right balance can lead to well-rounded knowledge, versatility, and the ability to tackle complex problems effectively. Many real-world problems are complex and multifaceted, requiring insights and skills from various domains. A breadth of knowledge and experience equips us with a solid foundation that supports us to see the bigger picture.

Everything, Everywhere, All at once.

As SAs, we are in the business of solving problems. This makes us very detail oriented and often very analytical. Much of what we have learned when designing solutions is to analyze the problem by breaking it down into smaller parts and addressing each of the parts. But by breaking things down, we lose the ability to see the greater whole, or to see the bigger picture (Think Big LP).

Think Big: Thinking small is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Leaders create and communicate a bold direction that inspires results. They think differently and look around corners for ways to serve customers.

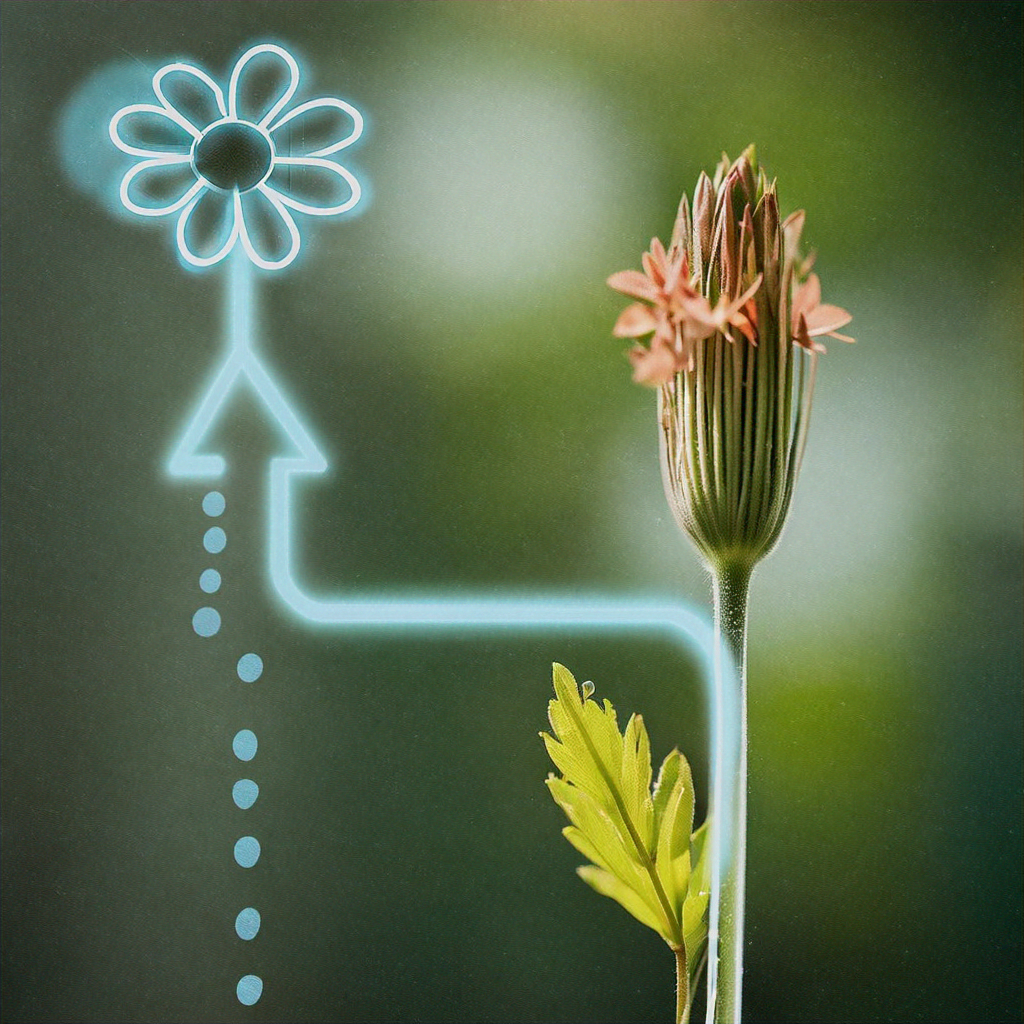

As children, we tended to have a much more intuitive understanding of systems. ‘System’ here does not mean “computer” or “software”, it refers to the interconnectivity of all things. If we show a picture of a flower to a child, they intuitively understand that it needs water to grow, the roots suck up water to nourish the leaves and bud, and the sun helps the bud to open and the seasons affect it. As children, we had an innate ability at looking at the bigger picture to intuit how the interconnectivity of things work. Unfortunately, most of us have lost that ability and only focus on how to rationalize, decompose, and break a problem into its smallest pieces.

Additional Reading: For the analyst in us, Systems: Definition and Observation

So, how do we take a step back and get a broader perspective of what’s going on? We could start by looking at the relationships between elements instead of the details of the pieces themselves. This concept is known as Systems Thinking.

The concept of systems thinking is closely related to the philosophical ideas of Holism: the view that the universe and all its components are intrinsically interconnected, and that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Each part exists in relation to and dependence on the whole. Systems thinking is a way of making sense of the complexity of the world by taking a systemic approach, looking at it in terms of wholes and relationships in the larger context of how patterns emerge over time, rather than the systematic approach of splitting it down into its parts to find, measure, describe, and evaluate each part according to an orderly process-driven plan.

Peter Senge explained it best in his book, The Fifth Discipline:

“Systems thinking is a discipline for seeing wholes. It is a framework for seeing interrelationships rather than things, for seeing patterns of change rather than static “snapshots.” …Systems thinking is a discipline for seeing the “structures” that underlie complex situations, and for discerning high from low leverage change.” - Peter Senge

The discipline of systems thinking is more than just a collection of tools and methods for analysis like we touched on in Why vs How, it is an underlying philosophy. Many SAs who start developing their Systems Thinking discipline are attracted by some of the more popular tools, such as causal loop diagrams or management flight simulators (Systems Modelling and Simulation), with the perspective that using tools will solve their most complex problems. But understanding systems thinking is more an understanding of the philosophical nature of interconnectivity and a sensitivity to the circular nature of the environment around us.

Systems thinking based analysis is more holistically diagnostic in contrast with traditional forms of analysis focused on identifying details and static states. Systems thinking emphasizes the relationships between parts of a system and how they evolve. Relating back to our “Why” and “So What”, this is where we focus our Root Cause Analysis outwards, instead of further stepping inwards, to provide deeper analysis to the question “Why” from a relational and interconnected perspective, and “So What” from a upstream/downstream causal perspective. Effective treatment follows thorough diagnosis. In this sense, systems thinking is a disciplined approach for examining problems more completely and accurately before acting. By understanding these diverse perspectives, we can make more informed and long-term decisions (Are Right, A Lot LP).

Are Right, A Lot: Leaders are right a lot. They have strong judgment and good instincts. They seek diverse perspectives and work to disconfirm their beliefs.

Systems thinking is how we can truly live our Leadership Principles - each of the LPs has to be used in balance with others. You need to have external awareness, a curiosity to explore, the willingness to see a situation more fully, to recognize that all things are interrelated, to acknowledge that there are often many ways to solve a problem beyond what is already known (“not invented here”), and to champion solutions that may not be popular.

What goes around comes around

If you dig deeper into system thinking (do it!), many authors and presenters will discuss the importance of defining what makes up a system in the framework of systems thinking by defining the Elements: the identifiable ‘parts’ of the system, the Interconnections: the physical and informational flows, and the Purpose: the observed behavior, not necessarily the ‘stated’ purpose. While this is a good primer for learning about systems, our experiences tell us that the secret weapon to understanding systems thinking is: feedback loops.

Feedback loops represent the circular causality and interdependence between different elements within a system. These loops illustrate how actions or changes in one part of the system can affect other parts, which in turn can reinforce or counteract the initial change. Feedback loops play a crucial role in understanding the behavior of complex systems and identifying potential leverage points for intervention.

The classic example of feedback loops is the “Limits to Growth” model developed by the Club of Rome in the 1970s. This model explored the interrelationships between population growth, industrial output, food production, resource depletion, and environmental pollution. One of the key feedback loops in this model is the reinforcing loop between population growth and industrial output. As the population increases, the demand for consumer goods and services rises, leading to an increase in industrial output. This, in turn, generates more employment opportunities and economic growth, which can further drive population growth, creating a reinforcing loop. However, this reinforcing loop is counterbalanced by other feedback loops related to resource depletion and environmental degradation. Increased industrial output leads to higher resource consumption and environmental pollution, which can ultimately limit the availability of resources and the planet’s carrying capacity. This, in turn, can constrain economic growth and population growth, creating balancing feedback loops that counteract the initial reinforcing loop.

By understanding the feedback loops and their interactions, systems thinking enables systems designers to anticipate potential unintended consequences and develop strategies that address the root causes of problems (Why vs How) rather than merely treating the symptoms.

Feedback loops are not limited to environmental or economic systems, they are found in many domains such as organizational dynamics, social systems, and most importantly technology adoption and software/digital systems. Where else have we seen feedback loops - maybe the Amazon flywheel? By considering feedback loops, we can gain a deeper understanding of the complexity of systems, identify leverage points for change, and develop more effective and sustainable solutions.

Thought experiment: Optimization of Solution Architecture (finding the feedback loops)

Given the business requirement:

Objective:

- Develop a subscription system to address the processing needs of data from external systems.

Functional Requirements:

Process requests in real time

Data storage for long-term request/response tracking

Problem space:

- As an integration, I want to submit data, in order to receive a processed result

- As an integration, I want to view previous submissions, to compare results

The solution space would require:

- API for integration

- logic to process data

- data store to store request and response data

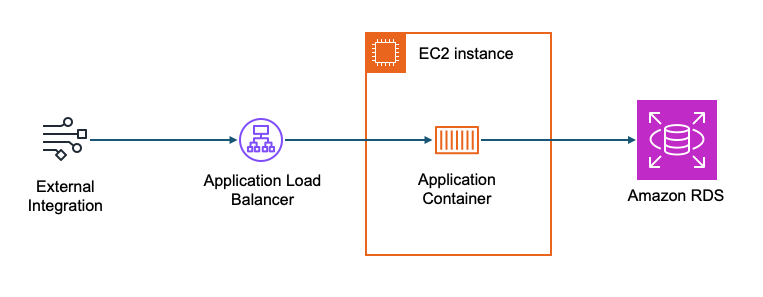

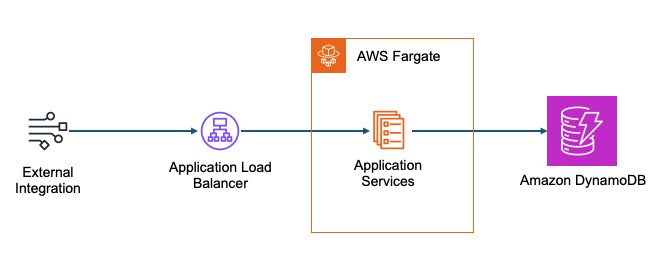

A basic functional solution design to the given requirements could be as simple as a containerized application on a single ec2 instance, connecting to a Amazon RDS data store, and an Application Load Balancer to handle the integration from external systems to make requests, such as that depicted in the diagram:

For the sake of brevity we will skip the elements such as VPC, Public and Private subnets, CIDR ranges, Internet Gateway, and all the security considerations of the design and take it that as SAs we all understand the basic foundations of a functional best practice AWS cloud solution.

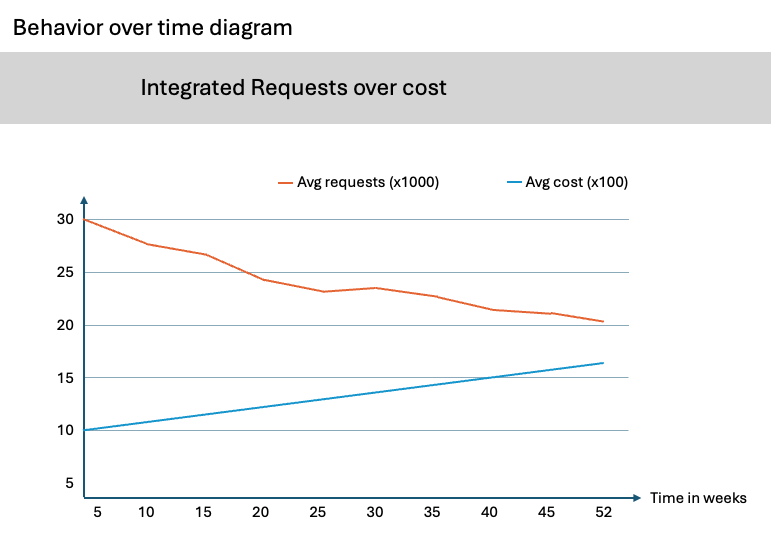

By observing the system over time and mapping out the Behavior Over Time Diagram, in this example used to graph the behavior of requests and costs over time, this gives us insights into the processes we want to map out in a Causal Loop Diagram.

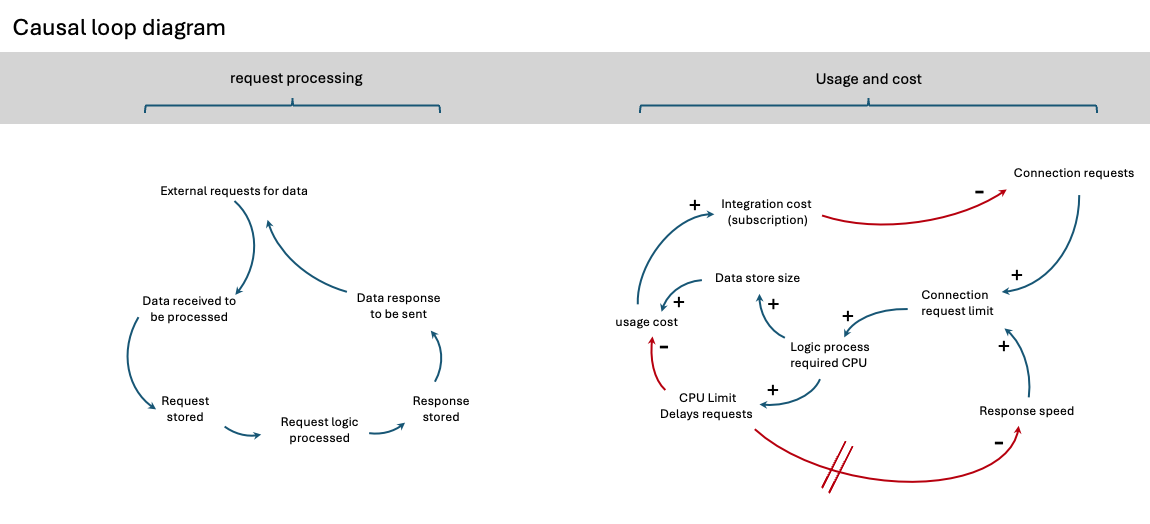

The Causal Loop Diagram maps out the basic elements of the system and the interrelationships between them, by mapping out the request and cost processes we are able to gain insights into the reinforcing and balancing processes.

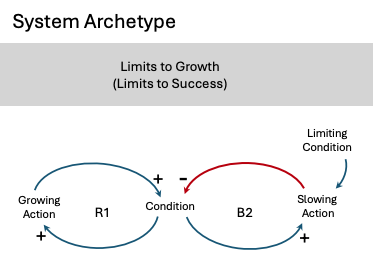

By using these systems thinking tools, we uncover the feedback loops and potential issues or bottlenecks in the systems operation, which weren’t apparent in the initial functional design. We can then map the observations to Systems Archetypes to help recognize common system behavior patterns.

In this instance, we might suggest that we are observing the “Limits to Growth” (aka “Limits to Success”) archetype:

The Limits to Growth archetype is the systemic representation of the Law of Diminishing Returns principle. Growth always runs into resistance, slowing growth. With every increase in effort to accelerate growth, resistance builds. At some point in the curve, the resistance of the limiting factors becomes greater than the strength of the growing action and growth stops.

With our knowledge of the “Limits to Growth” Archetype and understanding of the reinforcing (R1) and balancing (B2) feedback loops, the next iteration of the design might include looking at how to increase the CPU utilization, request limits to improve requests, and data store costs to reduce costs.

Now we have implemented AWS Fargate to manage the ECS cluster, and turned the containerized application into a scalable service, in order to handle more requests, both from a rate limit and CPU utilization perspective, and moved our data store to a DynamoDB table for basic key-value pair data, to reduce data storage costs.

Depending on your needs (informed by the business requirements), you could go through the process of analyzing the system again to observe additional emergent behaviors, map out causal relationships and observing behavior over time to find the new reinforcing and balancing feedback loops, and iterate on the solution design that further optimizes the performance of the functional output of the system.

This thought experiment highlights the importance of taking a systems thinking approach to solution architecture design. Simply fulfilling functional requirements is not enough; we must gain insights into the reinforcing and balancing processes at play. This leads to more optimized and resilient architectures that better address the business requirements while anticipating potential issues or constraints.

Conclusion

In technical solution architecture, it is crucial to embrace a holistic and interconnected perspective, which is the essence of systems thinking. While fulfilling functional requirements is undoubtedly essential, we must go beyond that and consider the emergent behaviors, feedback loops, and potential bottlenecks that may arise from the interplay of various system components over time. Failure to account for these interconnected dynamics can lead to suboptimal solutions that fall short of addressing the business requirements effectively.

Systems thinking enables us to step back and gain a broader understanding of the problem domain, recognizing that all elements within a system are intrinsically linked and influence one another. By mapping out causal relationships, observing behavior patterns, and identifying common archetypes, we can unveil the reinforcing and balancing processes at play, providing valuable insights for designing more optimized, resilient, and sustainable architectures.

The true power of systems thinking lies in its ability to anticipate and mitigate unintended consequences that may arise from our architectural decisions. Like ripples on a pond, our actions can have far-reaching effects that reverberate throughout the interconnected system. By adopting a systems thinking mindset, we can more proactively address potential issues or constraints, ensuring that our solutions are not only functionally sound but also capable of adapting and evolving in response to changing dynamics.

Ultimately, embracing systems thinking is not merely a set of tools or techniques; it is a philosophical shift in how we approach problem-solving and solution design. It requires us to transcend the traditional reductionist approach of breaking down problems into isolated parts and instead embrace the complexity and interconnectivity of the whole. Only by understanding the intricate web of relationships and feedback loops can we truly craft solutions that are resilient, adaptable, and aligned with the overarching business objectives.

Stay tuned

Enjoyed Systems Thinking Part 1?

In part 2 of systems thinking we will delve into the impact of the “infinite mindset”. Through thought-provoking examples we will demonstrate how embracing a holistic, interconnected perspective can lead to more robust, adaptable, and sustainable solutions. By understanding the intricate feedback loops, unintended consequences, and long-term implications of our decisions, we can transcend short-term thinking and cultivate a culture of continuous learning and innovation.

Whether you are a seasoned solutions architect or new to solutions architecture and interested in the future of technology and problem-solving, Systems Thinking Part 2 offers invaluable insights that will challenge your assumptions and expand your understanding of how to create enduring value in an ever-changing world. Prepare to be inspired by the transformative power of systems thinking and the infinite mindset.

Resources

Insightful Reads

- The Fifth Discipline - Peter Senge

- The Systems Thinker - Albert Rutherford

- Limits to Growth - Donella Meadows et al (Club of Rome)

Systems Thinking Tools

Dynamic Thinking Tools:

- Causal Loop Diagrams

- Stock and Flow Diagrams

- Multiple Cause Diagrams

- Behaviour Over Time Diagrams

- Applying Systems Archetypes

Structural Thinking Tools:

Computational Tools: